By Benjamin Lampkin

Someone once called my brother “that Spanish kid.” A woman in Greece looked me up and down and proclaimed, “You’re Brazilian, right?” For years, family lore posited that our grandfather was part Native American. When I worked at a country club in high school, a member apologized profusely to me after referring to Tiger Woods as the big bad “N word.” One of my endearingly naïve friends never knew I was a black kid until he saw me standing next to my dark-skinned father. My wife told me, not long after we first started dating, that she was into me partly because of my Mediterranean features. I’ve filled in the bubbles for black, African American, other, biracial, and multiracial on every kind of form and census and survey and application.

What I’m seen as and what I know I am is a recurring theme of my life and the lives of people like me, those with parents of different ethnicities and races and nationalities and colors.

But I’ve always been proud to have a black dad and a Greek mom and to feel a uniqueness shared only by me, my brother, and my sister. And when my son was born three years ago, I was excited to be able to pass along an affinity for all sides of my family, to be able to give him a sense of his African-American roots, in all its complexity and shades and history and terror and triumphs, as well as my mother’s deep and profound Greek heritage, and my wife’s American grab-bag of German, Italian and Irish ancestry.

This Christmas, after years of delving into my genealogical history with what little research I could muster online and the familial stories and photographs I’d grown up with, I decided a cool gift for my parents and my in-laws would be a DNA test through Ancestry.com examining the genealogy of my son, my little curly-headed, one-kid melting pot. Something fun. Something for the family to talk about. And, quite possibly, something unexpected.

This Christmas, after years of delving into my genealogical history with what little research I could muster online and the familial stories and photographs I’d grown up with, I decided a cool gift for my parents and my in-laws would be a DNA test through Ancestry.com examining the genealogy of my son, my little curly-headed, one-kid melting pot. Something fun. Something for the family to talk about. And, quite possibly, something unexpected.

I saw the email on Monday morning, Dec. 4, three weeks before Christmas, and well before I expected the results. Although Ancestry.com explained that the report would be available after six weeks or more, it had arrived in less than a month.

Thrilled, anxious, contemplative and unsure what to do, I waited another day to look.

Wasn’t assuming anything about my son’s results beyond what I knew, but the information loomed over me, ready to bash the conceptions of what I’d grown up to believe about my family. None of it would affect my three-year-old, and I doubted my wife would care much beyond finding out something interesting about her or my ancestry, but something was triggered in me, and my hesitation at seeing the results began to make sense.

For many biracial people, genealogy is a complicated subject.

Dawn Turner Trice, a former Chicago Tribune columnist, told NPR in 2008 that questions and issues of representation and identification for those with mixed ancestry have a “historical influence. Some members of the black community are a little sensitive about how biracial people identify themselves if one of the parents is black.”

Even the most well-known biracial man in history, President Barack Obama, self-identified as an African-American, after a long interior struggle, because of how others saw and treated him.

Even the most well-known biracial man in history, President Barack Obama, self-identified as an African-American, after a long interior struggle, because of how others saw and treated him.

But because I was so attuned to all aspects of my parents’ biographies, that struggle never materialized for me. Yeah, I identified myself as black because when you have a black dad, you’re supposed to follow suit, but I always believed myself to have the best of all worlds.

My dad is black, and his dad was part Native American, and my mother is white, but she is also a first-generation Greek American whose mom came to the United States as a student in the late 1940s and married my grandfather, a Greek Cypriot.

I was black and I was white, but I never needed to slap the latter on myself as a generic label because my mom wasn’t just white, she was Greek. To have a tangible connection to a place, a people, elevated me and my siblings above such a term.

The doubt was still there.

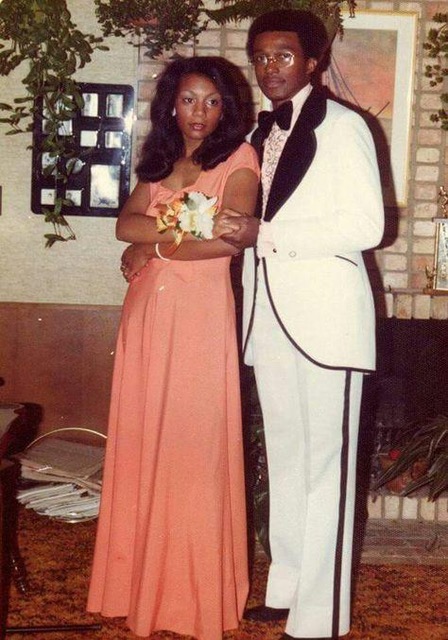

I kept waiting to look at the report, kept poring over family stories, and the cache of old black-and-white photographs my grandmother had entrusted to me. Stared at the dark faces, the great aunts and uncles, great grandparents, dark men in Army uniforms and wide-brimmed hats, women in fancy dresses and pearls, my grandmother and her best friend perched atop their bicycles, my great grandmother posing with the white family whose house she cleaned.

I knew some of the names and faces, many were a mystery, but the unexplored DNA test results seemed like a threat to all those who’d come before me, a genetic Magic Eraser set to wipe away the people who’d struggled and fought for a place in America, a place I know I take for granted.

I went to college on a full scholarship, studied journalism in graduate school, have worked as a sports reporter and a freelance writer.

Those pictures were of men and women who suffered to earn a living, fought in wars, shoveled coal for the railroad, poured molten steel for John Deere, cooked in family restaurants, operated a numbers game, farmed on land they didn’t own. I was afraid my son’s DNA would contain a startling lack of color. I was afraid he wouldn’t be black enough.

In his 2017 cover story for The Atlantic titled, “My President Was Black,” author Ta-Nehisi Coates examined the constant tightrope walked by President Obama during his eight years in office, the impact of race and identity that followed him during those two terms, and the very conscious decision he’d made decades earlier to enmesh himself in the African American experience. “If black racial identity speaks to all the things done to people of recent African ancestry, black cultural identity was created in response to them,” Coates wrote. “It is incredibly hard to be a full participant in the world of cultural identity without experiencing the trauma of racial identity.”

I’d seen that trauma firsthand, had experienced a little of it, but now wondered why I was so eager for my son to join me in this identity.

He isn’t as brown as me, and it’s doubtful he’ll ever be identified as African American like I’ve been, but I worried he’d be missing something if the numbers came back and didn’t reflect more of me, of my dad, of my grandparents, of those who’d endured so much.

I sat at the kitchen counter, finally ready, opened my laptop, signed into the website and clicked on my son’s ethnicity estimate. Saw the pie chart. The blue-tinged map. The colored circles representing all the regions of the world that my son was connected to. All sixteen of them.

It took me several moments to gather all the names, all the countries, to think of that little vial of saliva my son spent 10 minutes filling up suddenly spun into a kaleidoscope of ancestral homelands.

There they were.

The places. The connections.

Europe West. Europe South. Caucasus. Middle East. Great Britain.

Those five regions accounted for 75 percent of my son’s Ethnicity Estimate.

It was a lot, and there was no indication of any African blood.

Checked the rest, the “Low Confidence Regions,” when the predicted ethnicity percentage is less than 4.5 percent.

Saw Cameroon/Congo. Africa Southeastern Bantu. Mali. Benin/Togo. Ivory Coast/Ghana. Seemingly the entire continent, as well as a handful of percentage points from Europe East, the Iberian Peninsula, and Ireland/Scotland/Wales.

Did the math.

The racial arithmetic, along with everything my wife and I knew about the history of where our families came from, would determine the ethnic makeup of my son.

He is 31 percent German, which Ancestry folds into the Europe West region. I found out from my aunt that Caucasus and Middle East, which totaled 20 percent of his estimate, were included in her own DNA test results.

Must be a byproduct of our ancestors’ migration from Asia Minor to Greece and my grandfather’s homeland of Cyprus, located just 65 miles west of Syria and Lebanon. Europe South includes both Italy and Greece and accounted for 18 percent of the estimate.

When I added all the countries and geographic ranges together, it turned out my son is about 18 percent African.

I didn’t know why Great Britain popped up at a whopping 6 percent. I didn’t know why Ireland made a paltry 1 percent appearance, considering the supposed depth of my in-laws’ Irish ancestry.

Couldn’t figure out why the Iberian Peninsula and Europe East each snuck in at 2 percent. But the numbers were there, they were real, and I had to begin wrapping my brain around what it all meant.

Nothing.

Just numbers on a website. It meant nothing.

No. It meant everything.

Those numbers defined what my son was and, potentially, what he could be. I cycled through the possibilities, what the test meant to me, what it would mean to him, what I would tell others, what they would say about us. I had no answers.

I showed my wife the results, and she marveled at the 16 different ethnic regions, prepared to create a unique way to present the test as a cool gift to both sets of grandparents. She framed the map and ethnicity estimate for her parents, wrapped it for Christmas and I asked my in-laws to open the gift last that morning.

They were initially startled that we’d had the test done on our son, but my father-in-law examined the map and the numbers closely, curious about the disparity between the Irish and English percentages and the number of different African regions represented, and I saw a glimpse of highly-contained glee.

While he had questions and concerns about matters of privacy and DNA, given his medical background, he admitted that his only grandchild’s DNA was, indeed, fascinating.

I emailed the report to my parents and my siblings, received a small wave of texts and phone calls with some variation of “Wow,” “That’s neat,” and “How interesting!”

After taking a couple of days to process, more calls and texts came, first from my brother, who thought our dad should take a DNA test and is curious about his own kids’ ethnic makeup because of his wife’s Croatian background. And my sister and her husband were each highly enthused by the results and wanted to take a test. And my mom was surprised by the high concentration of German DNA versus her own Greek blood. And my dad commented on the minuscule African percentages present, though his interracial marriage, as well as mine, was one of the reasons why.

None of my family mentioned the absence of any Native American links in my son’s estimate. Not one measly percentage.

My initial reticence at looking at the results might have stemmed from the barely suppressed thought that those family stories were just that. I thought of Dr. Henry Louis Gates, the Harvard professor, author and filmmaker, who has commented on the hypotheses of many black families that insists there was an American Indian ancestor in their background. “The myth that we all have a Native American ancestor is one I encounter everywhere I go,” Dr. Gates said on his PBS series Finding Your Roots, and I realized I was also encountering it.

Outside of those tales, there was nothing in my amateur research to suggest my grandfather was descended from a Native American woman. No proof of any tribal affiliation, no records, no names, and there was no genetic evidence in his great grandson.

Kept looking at my son, trying to seize on some feature of his that would help offset the unease that had crept over me since I’d first seen the results. His blanched almond skin. His delicate, curly hair. That fat-bottom lip. Those espresso eyes. He didn’t look like a little black boy. Barely looked like a little mixed boy. He just looked like himself. Like me.

Maybe there is no tangible connection to a Native American ancestor; maybe his African American roots will remain hidden behind that ambiguous shading. That fear was back, the DNA results almost a confirmation that any links my son had with those black names and faces would fade away, become just a collection of photographs he’d never look at and stories of people he’d never meet.

It’s on me, then.

My wife will always be an important factor in helping my son embrace all aspects of his heritage, but I feel a sense of responsibility to be the catalyst for his lifelong immersion in the wide cultural identity that comes with this whole mixed thing.

Let him know those numbers and those percentages mean something, but they don’t mean everything.

He’ll always have a beautifully-tangled family history, myriad intertwined paths forged by slaves and immigrants and doctors and laborers and teachers that became this little boy.

But it will be up to him to take that history and build his own self, an identity unencumbered by the weight and expectations of DNA and ethnicity and genetics.

And I can’t wait to see what that looks like.

“It will be up to him to take that history and build his own self, an identity unencumbered by the weight and expectations of DNA and ethnicity and genetics. I can’t wait to see what that looks like.”