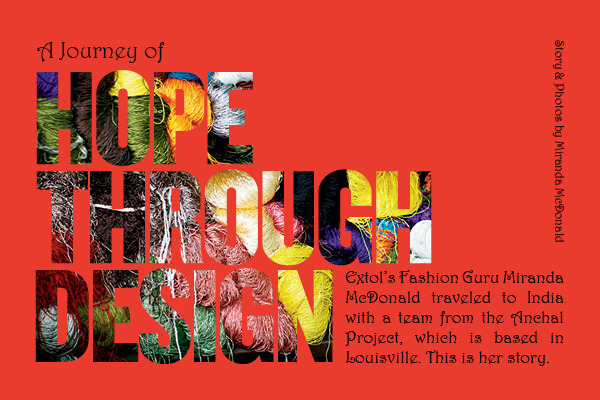

Story and photos by Miranda McDonald

“It’s difficult to describe this part of India to people, because you can’t understand what this country is really like until you have actually been here and experienced it,” Colleen Clines, the co-founder and CEO of Louisville-based Anchal Project, points out as our vehicle zig-zags its way through livestock, people and the occasional camel.

We are with a small group of people that includes Colleen’s mother, her sister, Maggie Clines, who is also the creative director at Anchal, and another writer from Kentucky.

As we make our way toward a local children’s village, I take a moment to reflect on the fact that I was sitting comfortably in the Nashville airport just two days ago. As I take in the atmosphere on an overcrowded highway somewhere between New Delhi and Jaipur, I anxiously wait for my first stop on a trip that will change the way I view the world forever.

ON A MISSION

In the the weeks leading up to my arrival in India, I spent several hours talking about Anchal Project and their mission. People were extremely supportive of me taking this trip to the other side of the world, but they didn’t seem to understand why I was going and what I would be doing there.

The weeks of preparation included an onslaught of questions, several vaccines and an arsenal of bug repellent.

With all this going on, I found myself feeling fascinated yet completely terrified by the many uncertainties that would accompany me on my journey. However, with every doubt that surfaced, and believe me there were several, I reminded myself that I had one important goal in mind: to help document the trip and share the organization’s story.

Much like Anchal’s co-founder, I didn’t realize just how life-changing my first trip to India would be. Colleen embarked on her first journey to India back in 2009 when she was working on her master’s degree in landscape architecture at the Rhode Island School of Design. She and three other women, including Anchal’s other co-founder Devon Miller, traveled to India to explore design in the developing world. It was during this trip that Colleen met Urmi Basu, a local leader from the New Light Foundation. Their interaction included a discussion on the economic oppression women face in India and how it kept them and their daughters in a continuous cycle of relying on work within the commercial sex trade to survive.

The graduate students also learned that more than 10 million women in India currently work in the sex industry because of poverty that ultimately stems from a lack of education. After learning about the extreme inequality these women face, Anchal Project, with its mission of using design as a springboard for social and economic change, was launched.

This inspiring story is what prompted me, a mere fashion journalist, to join the team on their annual trip to India. My goal was to share the organization’s story in a tangible way. And here I was in a completely foreign country, experiencing a culture vastly different than my own, eagerly anticipating our first stop at the Vatsalya Children’s Village.

I still remember wondering what my initial interaction with the people of this community would be like as we made our way down the dirt path that led to the entrance. As we pulled closer, I noticed a young woman waiting eagerly on the other side of the gate. Her name was Archana Paras. I would later find out that Archana was educated at Vatsalya, worked her way up to project director of Anchal Project and was the truest example of what the organization hoped to accomplish with with each woman it employed.

I still remember wondering what my initial interaction with the people of this community would be like as we made our way down the dirt path that led to the entrance. As we pulled closer, I noticed a young woman waiting eagerly on the other side of the gate. Her name was Archana Paras. I would later find out that Archana was educated at Vatsalya, worked her way up to project director of Anchal Project and was the truest example of what the organization hoped to accomplish with with each woman it employed.

Vatsalya, a non-profit that works to rehabilitate orphaned children, is funded through projects like Anoothi, an organization that trains women in the construction of clothing, jewelry and home décor items. Once Anoothi empowers these women with a new set of skills, they connect them with partners like Anchal Project in hopes of long-term employment opportunities. These opportunities allow the women to use their training in areas like sewing, pattern making and even in the art of woodblock printing, an occupation that is traditionally dominated by men.

After walking around the village, and meeting many of these women and viewing their work, we stopped by a small brick building that housed Anoothi’s extensive collection of woodblocks. While looking at these carved pieces of wood, I noticed that each had its own unique, intricate pattern. However, even if each of these blocks were completely different in design, they still managed to represented the collective voice of the women and the children of Vatsalya.

THE PINK CITY

The following morning, I woke up in Jaipur, the capital of the state Rajasthan. One little fact that I found to be particularly intriguing about Jaipur is that it is known as the “Pink City” because the stone that was used to construct many of its buildings has a slight pinkish hue. It is also said that Jaipur was given the title after Maharaja Ram Singh painted the entire city pink as a sign of hospitality when the Prince of Wales and Queen Victoria visited back in 1876.

I noticed the color of Jaipur’s magnificent structures when I visited the local market with the Anchal team. Colleen and Maggie, with the help of Paras and Anchal’s coordinator of research and development, Saloni Dangayach, were on the hunt for thread and other items that would possibly be used in future designs. I was simply following behind while watching, completely fascinated by the people of the city.

It still amazes me how so many people could fit into those narrow alleyways. Every couple of feet there was a vendor selling food, flowers or some kind of handmade goods. Horns honked at every turn, and rickshaws whizzed by, sometimes barely missing your toes if you were on foot.

People constantly approached us, hoping we would step inside their shop. It felt like complete chaos to a foreigner like myself, but somehow it all worked as a consistent flow of hustle and bustle for the city’s residents.

We also met Jaimala Gupta, the co-founder of Vatsalya and Anoothi. Her 12 years of work at the Indian Institute of Health Management Research in Jaipur led her to work as a mentor to the women of Anoothi and Anchal Project. She not only invited Colleen, Maggie and their guests (me being one of them) into her home to discuss the design workshops Anchal was hosting for the women in Ajmer the following week, but she also showed me the importance of chai tea breaks between talks of business, and invited me to try the spicy, cauliflower-based dish called “aloo gobi.” This invitation of breaking bread in her household made me realize just how important food can be when it comes to unifying people from vastly different cultures. Because, regardless of what language you speak, country you live in or religion you may embrace, the enjoyment of food is truly a universal pursuit.

Now, armed with an idea of what to expect from Anchal Project’s workshops and a food coma that only a home-cooked meal can induce, I was ready for the journey to Ajmer.

STITCH BY STITCH

There is a saying that every city has its own unique characteristics and tone that can easily be summed up in one word. Since hearing this declaration, I have subconsciously assigned a word to almost every city that I have visited. Some cities are harder to describe than others. However, Ajmer’s word quickly became obvious to me. It clings to everything it touches. It can be seen in the eyes of the women who work for Anchal. It can be heard in the playful shouts of the children running down the sidewalk outside of the women’s center and even in the smiles of strangers saying “Namaste” (the Hindi word for hello). It even resides in every stitch that is placed on an Anchal quilt. This word, Ajmer’s word, is hope.

Creating a collection like the Narrative Collection starts with the training that happens during the Anchal Project workshops. Each of the artisans are given the measurements and patterns needed to construct templates for the individual pieces of fabric that they will be stitching together for each quilt, pillow, scarf and poncho. The organic fabric is then carefully cut into panels and sewn together. This step-by-step process not only results in the creation of a beautiful piece, but it also teaches the women how to problem solve and work together through the medium of textile and design. This teamwork gives them a sense of community and a real chance to regain the pride that was once stripped from them. This pride is also built into all of the one-of-a-kind creations they construct year-round from the repurposed saris they find at the local markets.

Creating a collection like the Narrative Collection starts with the training that happens during the Anchal Project workshops. Each of the artisans are given the measurements and patterns needed to construct templates for the individual pieces of fabric that they will be stitching together for each quilt, pillow, scarf and poncho. The organic fabric is then carefully cut into panels and sewn together. This step-by-step process not only results in the creation of a beautiful piece, but it also teaches the women how to problem solve and work together through the medium of textile and design. This teamwork gives them a sense of community and a real chance to regain the pride that was once stripped from them. This pride is also built into all of the one-of-a-kind creations they construct year-round from the repurposed saris they find at the local markets.

Currently, Anchal Project employs more than 150 women, and each year that number grows. These annual workshops provide training for the existing women, and they also provide an opportunity for other women in the surrounding communities to come in and show their skillsto the Anchal team. In hopes of gaining future employment by Anchal, they sit in on a day-long workshop that gives them a chance to show their sewing skills and allows them to meet all the other artisans.

MEANINGFUL CHANGE

Before leaving the women’s center on my last day in Ajmer, I sat legs crossed on the ground alongside a few of the Anchal artisans who were ironing fabric that had just come in from the market. Their cheerful banter served as the soundtrack for the moment.

Colleen walked over to inspect a beautiful red sari that boasted a golden floral pattern. “The anchal is the decorative edge of the sari. It is said to provide protection to the women who wear it,” Colleen explained as she lifted the fabric to show me the large flower adorning the fabric’s edge.

In that moment, sitting amongst the women, I realized just how fitting Anchal’s name really is. Yes, Anchal Project – an organization based in Louisville – is providing protection to these women and their families by giving them economic opportunities in a country where there aren’t many. But, their reach truly expands the borders of any one country.

Anchal is at the forefront of a growing movement that will shape a new generation of companies that are acutely aware of their own social and environmental footprint. They are leading the way with the radical idea that beautiful design can be a driving force behind meaningful change, and this wonderful notion is one that can bring hope to all.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Anchal Project

info@anchalproject.org

201.855.6597

Anchal, Inc. PO Box 7392

Louisville KY 40257