Former University of Louisville Basketball player Robbie Valentine talks about the hard facts and personal fouls he’s experienced off the court.

By Steve Kaufman | Photos by David Harrison

What could have been Robbie Valentine’s story gets played out hundreds – thousands? – of times every year.

The product of a single-parent family – whether from a small rural town or large inner-city – finds out early on that he is gifted at basketball (or another sport), which leads him (or her) to the path of a big college program.

There, he single-mindedly focuses on a professional career, puts his name in the draft and, maybe, he’s a lottery pick. Or at least a first-round pick. But maybe he’s a second-round pick, with less signing bonus and practically no contract guarantees. Or, he’s not drafted at all. So, he rides the D-League buses from Erie to Ft. Wayne to Des Moines, hoping to get noticed by the big-league teams, and hopes, too, to stay healthy. Because if he’s injured and his career is jeopardized, what’s he going to do with that one year of college and a once-famous name that’s now gathering some rust?

SCREEETT!!

That’s the sound of the phonograph needle grinding to a halt. Because, while it’s a way-too-familiar story, it’s not Robbie Valentine’s.

It could have been. But Valentine saw something else along the way. He saw a Radcliff, Ky., mother who raised seven children by herself, working in the local schools and cleaning other people’s houses to make sure there was food on the table and clothes on her kids’ backs.

Frances Valentine also instilled far more in her children: faith, self-respect and the  value of education – that there was a world out there, beyond sports, even for her oldest son who was breaking all North Hardin High School basketball scoring records.

value of education – that there was a world out there, beyond sports, even for her oldest son who was breaking all North Hardin High School basketball scoring records.

Of course, Valentine came along at a different time. Back then, there was no one-and-done. College coaches had time to nurture and mentor their players. Valentine needed that mentoring. He had been a high school All-American. The sky was the limit. But jumping for the sky was his downfall.

“When you jump high and come down, you put a lot of pressure on your tendons,” Valentine recalled. “Back then, we wore Chuck Taylors, Pro-Keds, Converse. Those shoes weren’t made for jumping.”

Valentine started seeing Dr. Rudy Ellis, the noted Louisville sports medicine physician, as early as seventh grade. “My file became very thick,” he said. “I popped both Achilles tendons, ended up with surgery on both knees. Plus, I had four screws in my back.”

But, along with his medical problems, Valentine developed a remarkable perspective for someone so young.

“When he came here (to the University of Louisville), he had a lot of natural talent,” recalled his Cardinals coach, Denny Crum. “But he also had a great attitude. Even as a freshman, he was a leader. Everyone respected him.”

Early on at Louisville, Valentine was playing only a few minutes a game. “I now realized I wasn’t going to make it to the NBA,” he said. “So why continue to dream for something you know isn’t going to happen?”

He began to see basketball as an opportunity toward something else. “It was going to help me get my college education,” he said. “I wanted to make it in the job world, someone who could speak, who could write, who could read, who could talk to anyone at any level.”

Crum instilled in him the idea of service to others. “He’s done more for his community in Louisville than anyone I know,” Valentine said, “and (Coach Crum) shaped our lives to do the same.”

Then there was the group of freshman basketball players who arrived on campus in the fall of 1982, shortly after Louisville won the 1980 national championship.

“I came in with Milt Wagner, Billy Thompson and Jeff Hall,” Valentine recalled. “When we were freshmen, seniors Rodney and Scooter McCray sat us down and said, ‘This is our senior year, but you guys are the people who’ll help us get there.’ And we did go to the Final Four that year.

“So four years later, Milt, Billy, Jeff and Robbie, we were the four seniors. And it was up to us to change the lives of those new freshmen kids, led by Pervis Ellison.”

“We could tell we had a great team, but it was young,” said Crum. “Robbie and the other seniors helped keep those freshmen in line.”

It was then that the four seniors came up with the word that would bind them for the next 30 years, changing the way Valentine began to live life.

“We seniors told the freshmen that the one word driving us all was ‘live,’ ” said Valentine. “Before every game, before practice, after practice, in the locker room, during time-outs, our chant was ‘one-two-three-live!’

“What did that mean to them? “When you grow up in a three-bedroom home with eight people, it’s pretty tough,” said Valentine. “Though all the odds were against us, to be able to live the life we lived and to make it as 22-, 23-year-old seniors, that’s pretty incredible.

“We weren’t supposed to be there. We all had some tough times at home. We wanted to make a difference, in school, on the team, in the community. Our goals were to make the next person better than we were, starting with those freshmen.”

They Did, Of Course

On March 31, 1986, Louisville beat Duke 72-69 for the national title. But the injury-hampered Valentine, who’d played only 41 minutes that entire season, did not get into that game, but he was on to his next phase of what it meant to live. “My focus had become: What is Robbie Valentine going to do to become more successful in the community?”

He studied education in college, and then earned a master’s in sports management. He became Crum’s graduate assistant coach. He joined the broadcasting team for Louisville games on WDRB.

“He had the desire to succeed, and everyone knew and liked him,” said Crum. “I couldn’t wait to see what Robbie would do with his life.”

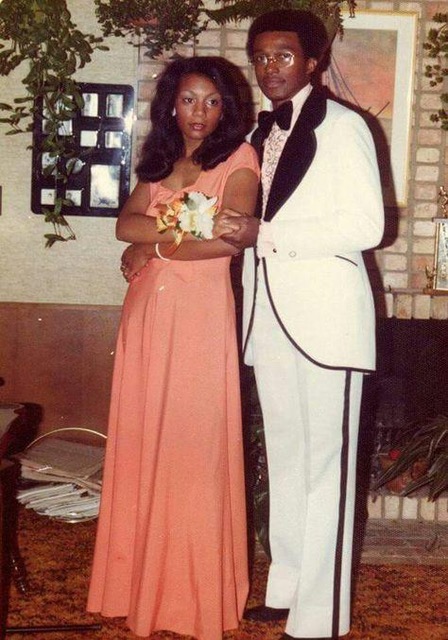

“The way I took it was, the more education I got, the more doors were going to  open up for me,” Valentine said, “and the more doors that opened up for me, the more important people I’d meet, and that would help open even more doors.” He also got married in 1989, to college schoolmate Beth Kantor, and almost immediately had identical twin boys, Eric and Aaron. Daughter Brooke came along in 1993.

open up for me,” Valentine said, “and the more doors that opened up for me, the more important people I’d meet, and that would help open even more doors.” He also got married in 1989, to college schoolmate Beth Kantor, and almost immediately had identical twin boys, Eric and Aaron. Daughter Brooke came along in 1993.

He launched Robbie Valentine Enterprises, running education programs – such as basketball camps – throughout Jefferson County and Southern Indiana. “We got some large grants for the work we were doing, and it was pretty successful,” he recalled. “I was determined to pass on the values that I’d learned as a youngster, so we required kids to go to class and study if they wanted to participate in the program, just as I had.”

Dejuan Wheat passed through Valentine’s program. So did Sara Nord. But the program was not only for the superstars, it was for any kid from the streets.

“When I started playing basketball through the Stithton Baptist Church in Radcliff, our pastor, Gene Waggoner, said that if we wanted to participate, we had to be a ‘Royal Ambassador.’ That meant attending Sunday School, being in choir, joining the youth group.”

In other words, you had to get involved and fully.

Valentine further walked the talk he’d learned by joining the board of the Greater Clark County Schools.

Robbie Valentine’s life was on-track. And then, suddenly, it wasn’t.

He was divorced in 2004. In 2008, the economy began to crumble and the grants dried up. In 2010, Robbie Valentine Enterprises Inc. filed for bankruptcy.

And that summer, he was arrested for a DUI in New Albany.

Life Intrudes

As is often the case, the actual details are murky. According to Valentine, he left a New Albany establishment after dinner around 7 p.m. on a July evening and was soon arrested for driving under the influence. Eventually, the DUI was dropped and he was charged with reckless driving.

While the details were ambiguous, the newspaper accounts were not: “Robbie Valentine pleads guilty to reckless driving. The former University of Louisville basketball player and current Greater Clark County School Board member won’t go to jail for his drunk driving arrest.”

Back on the Ladder

“That was a low point for me,” he said. “Divorce. Bankruptcy. Headlines. To get out of that, I went back to the past, and started thinking, ‘What do you do when you fall off a ladder? You take one step at a time to go back up.’ ”

All the contacts and networking Valentine had done, the support system he was  able to build, started kicking in. Following a recommendation by Crum, he got a phone call from the Kentucky State Fair Board, offering him the opportunity to work for the KFC Yum! Center as assistant general manager.

able to build, started kicking in. Following a recommendation by Crum, he got a phone call from the Kentucky State Fair Board, offering him the opportunity to work for the KFC Yum! Center as assistant general manager.

“It’s the best job in America,” he said. “I love customer service, marketing, public relations and, of course, Louisville basketball. I’m involved with an amazing team of employees. And I get to deal every day with some of the best people in Kentuckiana and around the world.”

He also revived his youth basketball camps, although now he conducts them during the summer at the Yum! Center. He also does free camps around the area during the summer and the Christmas break, sponsored by the likes of Papa John’s Pizza and Vision Works. Participation at the Yum! Center camps is based on school attendance, grades and behavior.

“My program is identical to what Mom’s vision was when I was a kid, and my preacher, and my high school coach,” he said. “I put it all together and now I’m doing all the work they did for me to this day.”

Life Intrudes Again

But another low point was about to send Valentine reeling again. He had been divorced from his first wife in 2004 and, in 2010, married his second wife. In June of 2016, they were separated.

The divorce came through in October. Valentine was devastated.

“I think a lot of our issues were due to our similar childhood situations growing up,” he said. “A lot of times, when you don’t grow up in a normal family environment, it can affect you in different ways. I really believe that some of the things I dealt with as a young person made our marriage tough.”

Equally rough for Valentine was dealing with his divorce. “It really hurt me. When you go through those things, you have to find ways to pick yourself up. It’s that ladder thing, again.”

And so he turned to what would give him strength – his friends and his church.

Having Faith

“I’ve been with Northside Christian Church in New Albany for six years,” he said. “George Ross and Nate Ross, the senior and associate pastors, have been absolutely my rock, the ones I could talk to about anything or everything. And they’d pray with me, or just listen to the hurt.”

“A person has to want to get well,” said George Ross, referring to the story in the Bible of Jesus at the healing waters of the pool of Bethlehem. “The paralyzed man said to Jesus, ‘I have no one to help me into the pool,’ and Jesus asked him, first, ‘Do you want to get well?’

Did Robbie want to be a survivor,” said Ross, “or remain a victim and blame everyone else?”

The two pastors led Valentine to the church’s 18-week Divorce Care course. “Divorce Care helps people process their hurt and brokenness,” said Ross. “It lets them know they’re not alone.”

“You discover hope and experience healing in a group setting every week,” said Valentine. “We talk about everything, all the hurt, the pain, the emotions, the anger, the shame, the ups and downs. The feeling is almost like death, except that the other person’s not dead, you’re still going to see her.”

Partly for that reason, Valentine chose to stay away from places where his ex-wife might well be, as well as where he’d be faced with an alcohol-fueled atmosphere. “I chose not to go to clubs, bars, environments where alcohol could be a 100 percent downfall for me,” he admitted.

“When people go through tough times, sometimes they drink and do other things because of the hurt they’re going through,” he said. “That doesn’t make you heal. It might make you forget for a few hours, but you’ll wake up with the same problems.”

Besides, he said, “I chose to go faith-based; (I’m) not interested in dating. They teach you to wait and heal before you get back in a relationship. If you’re not healed and you go straight into a relationship, what are you doing to yourself and to your partner?”

The Rock and the Ladder

Another rock for Valentine was Jim Shannon, the successful basketball coach at New Albany High School (last season’s Southern Indiana coach of the year).

“He saw my hurt. We went to the Outback in Clarksville, and he just listened. Sometimes all you need is a listener. And we can use basketball as a way to talk about the positives and the negatives. Sometimes, it’s good to lose, because when you lose, you learn what winning means.”

Overall, though, Valentine chose his support group carefully. “You want to be around as many positive men as you can, but you have to be careful how you choose to speak to women.”

If he wants a woman’s input, he said, he can talk to one of his five sisters. But he doesn’t necessarily expect sympathy.

“My family will sometimes tell me what I don’t want to hear,” he said. “They’ll say, if I’m going to whine and cry, don’t go to them.

“They’re tough!” With his faith firmly in place, Robbie Valentine has been rebuilding his life – or, with the analogy he likes to use, getting back on the ladder, step by step, and returning to the lessons he learned early in life – about commitment, perseverance and values from his boyhood pastor, Gene Waggoner, and his high school coach, Ron Bevers.

But most of all, there was his mother. A hard worker, a disciplinarian, believer in family and faith.

“When I think of my life as being difficult, I think of her. Difficult? My mom worked three jobs to raise seven kids by herself. That’s difficult. By comparison, my life has been blessed,” Valentine said. “I derive my faith from God and my strength and inspiration from her.”