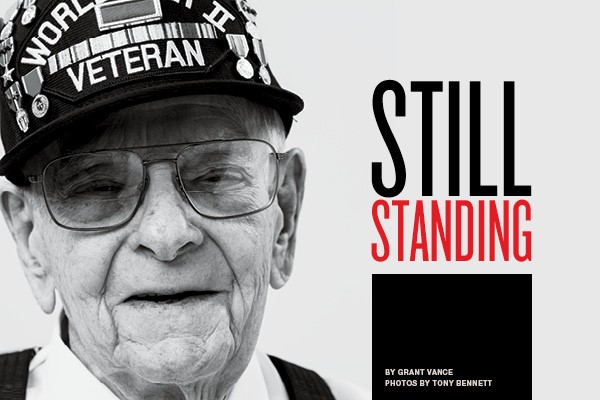

By Grant Vance | Photos by Tony Bennett

Meet Edward “Duke” Roggenkamp Jr., a 95-yearold World War II veteran who is still standing, despite the dour reality: According to the Veteran’s Administration, World War II veterans are dying at a rate of approximately 492 a day. This means there are approximately only 855,070 veterans remaining of the 16 million who served our nation in World War II. Their stories are important, and we were lucky enough to spend a few hours with Mr. Roggenkamp, a longtime Milltown resident, who shared harrowing tales of war, heart-warming love for his family and country, and proof that age is just a number.

A young man, just a year out of high school, walked into the Milltown movie theater with his girlfriend just after hearing the news of the bombing of Pearl Harbor over the radio. Turning to the crowd inside of the theater, he announced what he’d heard: Japanese bombers have attacked American soil.

A young man, just a year out of high school, walked into the Milltown movie theater with his girlfriend just after hearing the news of the bombing of Pearl Harbor over the radio. Turning to the crowd inside of the theater, he announced what he’d heard: Japanese bombers have attacked American soil.

America is going to war, Edward “Duke” Roggenkamp, Jr. knew, and, due to the nature of the draft, so was he.

Today, Roggenkamp is a 95-year-old World War II veteran who is too humble to acknowledge himself as a hero. In his eyes, he simply “worked in earnest to do what (he) was trained to do.”

Despite his heart-warming humility, many would agree he downplays the state of his heroism, both in service and to his own family. “He’s the kindest person,” said his daughter, New Albany resident Rebecca Vance. “I couldn’t have asked for a better father.”

JANUARY 1945

It’s January 1945 and 23-year-old Roggenkamp is on a transportation convoy between Sansapore and Lingayen Gulf off the coast of the island of Luzon, home to Manila, the main capital of the Philippines. He recalls the jarring alarm from the ship’s loud speakers, calling for the soldiers to man their battle stations. He looked up to see five black specks in the sky. “Japanese (kamikaze) planes coming out of the sun,” Roggenkamp recalled. “I didn’t know where all of them went, but I knew where one of them went. …It was so close I could see a grin and smile on (the pilot’s) face.”

Narrowly passing Roggenkamp’s ship, the plane dropped two bombs on either side of the ship directly to his right before completing a U-turn and crashing into the ship’s super structure, causing “fire and explosions.” The convoy is “three ships wide and nine to ten long,” Roggenkamp said. “You couldn’t see the front ships or back ships.” The side ships, however, were merely “a quarter mile away; very visible.” He saw 40 to 50 sea burials the next day.

These men are among 400,000 American soldiers who lost their lives serving during World War II – roughly 70 of which lived in Roggenkamp’s hometown of Milltown, a town in Southern Indiana.

Fort Knox, as well as Camp Grant in Illinois, are two of several camps where Roggenkamp trained as a wheel vehicle mechanic during the stateside service portion of his enlistment. He also trained in several other camps around Texas and California with the 424 Medical Collecting Company, his assigned unit responsible for supporting the 1st, 6th, 25th, 32nd and 37th Calvary Divisions by providing “treatment and evacuation of wounded and sick combat troops.” As a member of the 424, Roggenkamp along with his “unusual medical unit” were responsible for tending to the front lines. Personally, he acted as the unit’s motor pool vehicle mechanic, responsible for 19 vehicles including 12 ambulances – several for company supplies and several for personal transportation and supplies. He has a very high mechanical I.Q., leading him to be the top field mechanic in his unit. “(The vehicles) went through tough terrain, sometimes salt water, sometimes creeks, sometimes rough gravel,” he said. “But you gotta keep running.”

The conditions of the war were dire, Roggenkamp said, describing the lifestyle as living “day-to-day awaiting orders,” moving from foxhole to foxhole eating and sleeping on the fly. “You didn’t feel much of anything,” he said. “(It was a) lost feeling. … We were bombed so often that we (had a betting) pool every day. If you picked the time closest to the first bomb dropped you won!” he wrote in his short, self-published memoir, Duke’s WWII Stories. “What a way to have fun! Something only a G.I. would understand!”

When not surrounded by enemy bombs – one landing within 25 feet away that permanently damaged his hearing – Roggenkamp was dodging gunfire. He described one retrieval mission in particular: “My commander said: ‘My jeep’s clutch is stuck. I need you to get it,” Roggenkamp recalled. “I said, ‘Yes sir, but I need a driver.’ ”

He tells the story triumphantly, describing his close call and quick thinking. “The clutch was stuck so (we) had to attach a cable to the front (to get) momentum going,” he said. “I got on the hood and heard budd-da-da buddda- da budd-da-da budd-da-da. Four shots. They were firing at me.” Friendly infantry finally caught up with him, throwing a grenade that ended the enemy gunfire. Despite everything, he accomplished his mission, making it back to the rendezvous with his driver.

“It was a horrible and emotional time for the soldiers,” Vance said, reflecting on her father’s time overseas. After retelling his anecdotes of consistent onslaughts of enemy bombs and gunfire throughout the Philippines, harsh swamp-like conditions in New Guinea and a near-invasion of Japan on the cusp of their surrender, Roggenkamp solemnly nodded in agreement.

War is a harrowing, nasty beast that consumes all too many good soldiers in its clutches. Yet, as Roggenkamp can attest, there’s also hope and longevity despite it. For one year, 10 months and 6 days he trained under Continental Service, which helped to prepare him for a year, 7 months and 24 days of Foreign Service. These 3 and a half years define him as a veteran, but they don’t come anywhere close to defining the Nascar-loving, kindhearted, family-oriented man that he’s been for a far greater portion of his life; 95 years is a long time to be a hero.

RETURNING HOME

Experiencing the horrors of war take a toll, but Roggenkamp doesn’t let his time of service – he was drafted June 6, 1942 and honorably discharged Dec. 5, 1945 – stop him from living a fulfilling life and making a positive impact on those around him. Once his honorable discharge went into effect, it wasn’t long before Roghenkamp’s departure from Japan.

He returned home to Milltown, where he ran a Chevrolet dealership for 57 years and raised a family alongside his wife. Rebecca (Roggenkamp) Vance is the middle of three children, born in 1949; the oldest, Edward Karl Roggenkamp III, was born in 1944 while Roggenkamp was still overseas; he was 18 months when they first met. The youngest, Kelley, was born in 1959.

Edward “Duke” Roggenkamp was awarded many decorations and citations, including American theater ribbon, Asiatic-Pacific theater ribbon, W/2 bronze stars, Philippine Liberation ribbon, W/1 bronze star, Good conduct medal, Meritorious unit award and Bronze Arrowhead Victory medal World War II; every ribbon receiving a corresponding medal. These decorate his hat proudly, standing as a physical symbol of triumphant hardship his stories hold.

Roggenkamp was happily married to his wife, Kathleen, for 68 years before her passing on September 11, 2011. Both Roggenkamp and Vance speak very highly of their wife and mother, respectively, who they remember as the “unofficial mayor of Milltown.”

In his time after service Roggenkamp stayed very involved in his family and the community. In fact, he’s been a due paying member of the American Legion Milltown Charter for 72 years, making him the oldest living due paying member. “He’s very well-known,” Vance said. “All the women of Milltown want to hug him. … He never let his feelings he brought home with him (affect) anyone else. He’s always been a kind caring person.”

The respect and admiration for her father – and mother – is even more evident today. “Him and mom didn’t just retire and sit in chairs,” Vance said. “And he still uses a cell phone. Pretty impressive for 95.”

AH, 95.

Less than five years from a century of living, Roggenkamp is in high spirits, his top priorities to simply stay “comfortable and careful” and keep up with Nascar, which he loves so much.

For his 80th birthday, the family pitched in for a driving session at Kentucky Speedway in Sparta, Ky. “I was in my driving suit and my helmet,” he said. “By the tenth rep I was up to 150 miles per hour.”

Vance remembers the day very fondly. “They let the whole family (drive around) on the track,” she said. “It was so much fun.”

Today, Roggenkamp remains strongly invested in the state of the USA, holding true to the value of freedom. “(There are) too many people who don’t know how to control freedom or what to do with it,” he said. “I listen to both sides of politicians and this, that and the other. … We need to elect people who you know will keep the country’s freedom alive.”

Yes, Roggenkamp plans to vote in the November election, but it’s not the party or person Roggenkamp particularly cares about. His utmost concern is that the nation remains grounded in freedom. “People (should be) living the lives they want to live.”